Strong earthquakes, erupting and spluttering lava and toxic gas has shaken the residents of southern part of Big Island of Hawaii as magma shift underneath a restless Kilauea Volcano.

The residents of the big island Hawaii react to this natural disaster with grief and reverence. According to Hawaiian legend, the Halemaʻumaʻu crater at the summit of the Kīlauea volcano is home to the Pele-Hawaiian goddess of fire, volcanoes, and lightning and wind. Referred to as madam Pele or Tutu grandmother – Pele is regarded as the powerful force behind Kilauea's decades-long eruptions.

|

| Goddess Pele, Image from Jaggar Museum, Hawaii |

Hawaiian people believe that sometimes Pele needs to clean the land and the eruption, lava, and ash flow are all her ways of teaching people how to live on the islands.

It’s she who makes the decision that where the lava flows and how the land is shaped for future generation. It is believed that Pele is out to reclaim the land that was taken from her. At the end of the day, Pele will take what is rightfully hers.

The residents are offering Ho’okupu of Ti leaves in front of lava flow to the fire goddess to calm her down as they prepare to leave their homes in Leilani estate.

Timeline of the current eruption

|

| In this photo released by the U.S. Geological Survey, lava is shown burning in Leilani Estates subdivision near the town of Pahoa on Hawaii's Big Island on Thursday |

Kilauea is Hawaii’s most active volcano and has been erupting continually since 1983. Hawaii officials have been warning the residents in Puna, Big Island Hawaii since Monday, April 30 that they should prepare to evacuate since an eruption can come anytime from the mighty Kilauea. This warning came after the Puu Oo crater floor began to collapse on Monday, triggering a series of earthquakes and pushing the lava into new underground chambers towards the populated southeast coastline of the island.

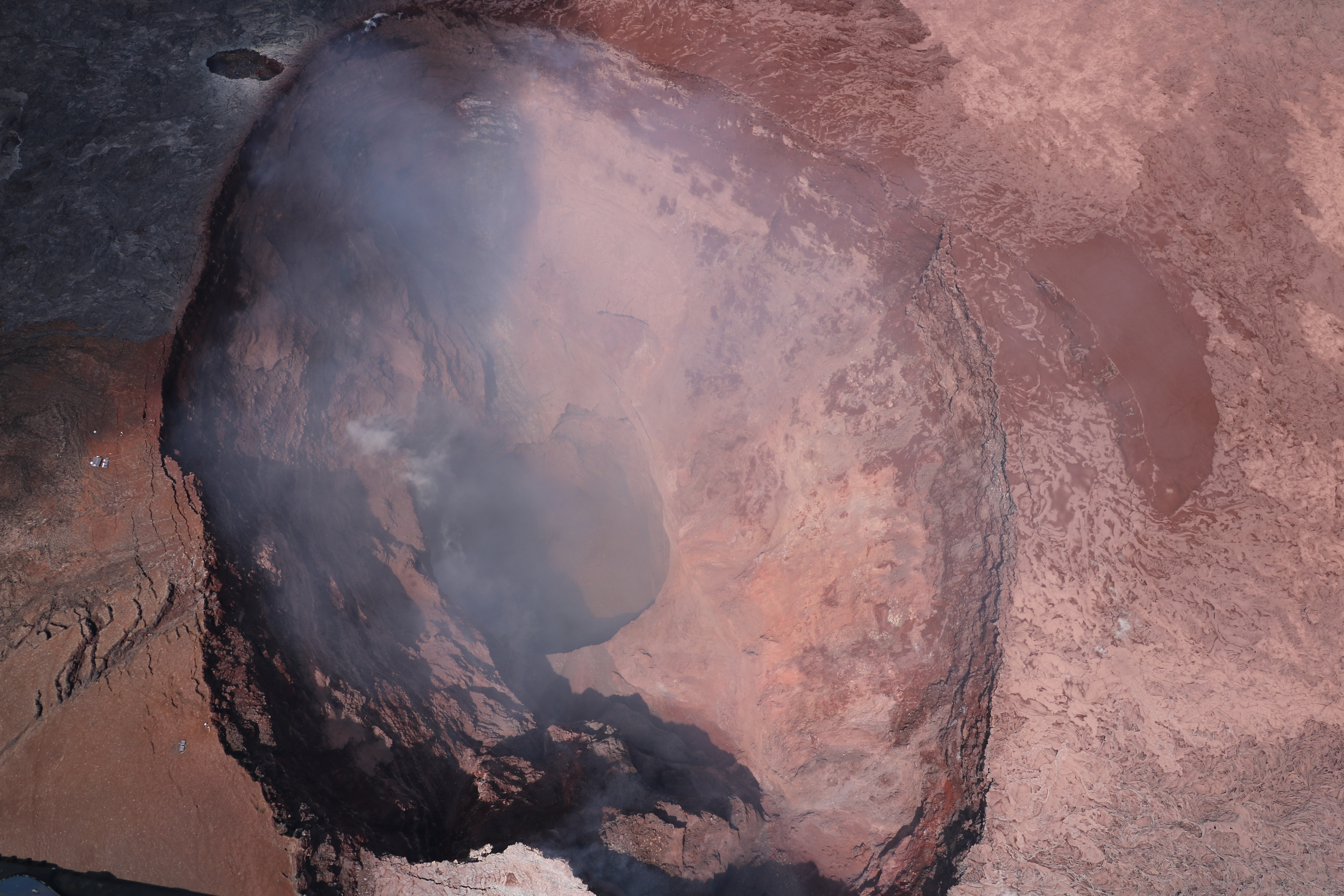

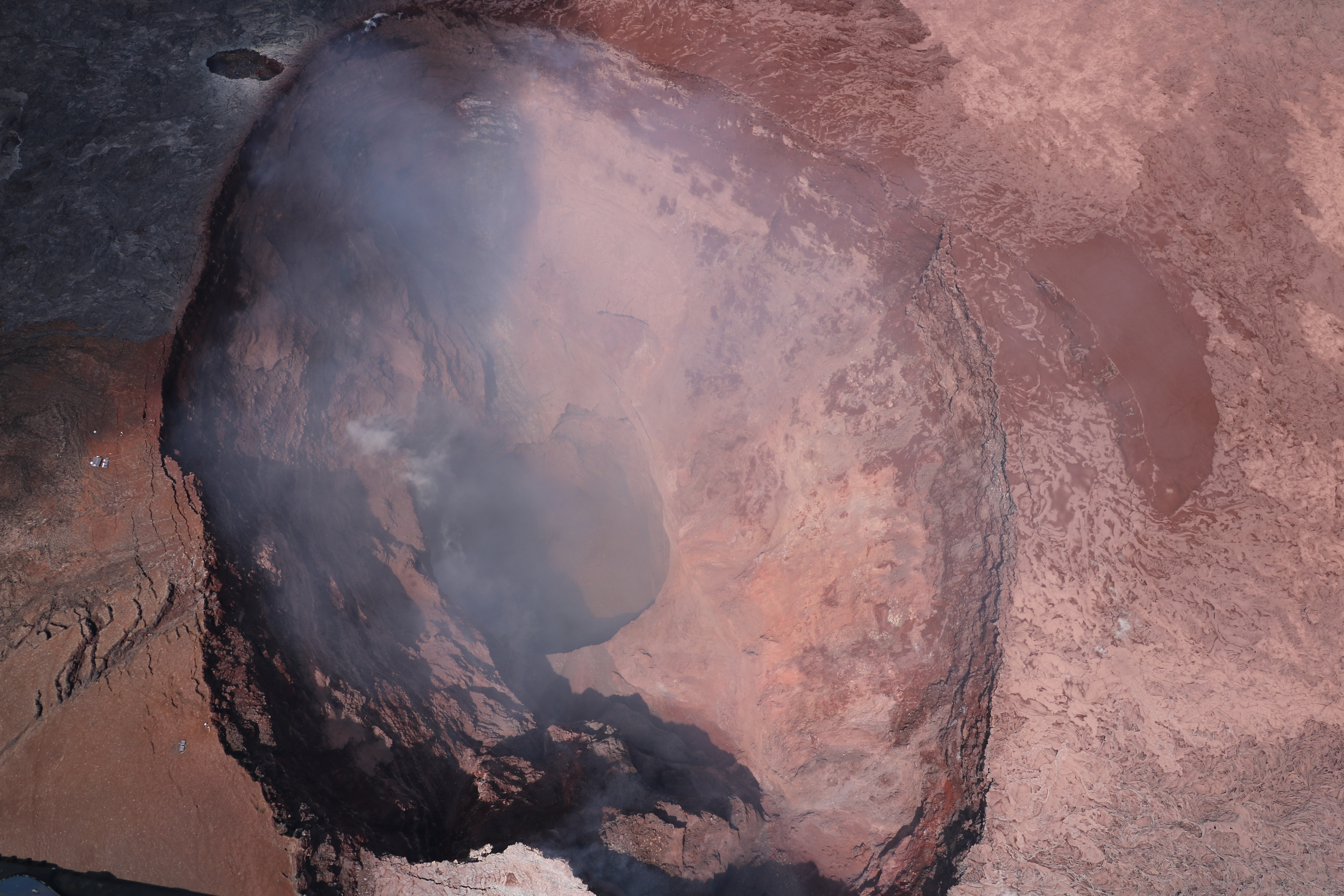

|

| A clear view into Pu‘u ‘Ō‘ō crater. The upper part of the crater has a flared geometry, which narrows to a deep circular shaft. The deepest part of the crater is about 350 m (1150 ft) below the crater rim. |

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, there were nearly 70 earthquakes of magnitude 2.5 or stronger from Tuesday to Wednesday alone.

The Monday collapse caused magma to push more than 10 miles downslope toward the populated southeast coastline of the island.

The eruption first started on Thursday, May 03, 2018 several hours after a magnitude-5.0 quake struck the Big Island. The eruption spewed lava into residential subdivisions in the Puna district of the Big Island, prompting mandatory evacuations of the Leilani Estates and Lanipuna Gardens subdivisions.

As of today, 20 fissures have opened since May 3 in Kilauea’s east rift zone, where a few small subdivisions have been built in recent years. The lava from them has shot hundreds of feet into the air, swallowed cars, destroyed about 27 homes, and forced around 2,000 residents to flee.

- Some 37 structures have been destroyed

- Lava has covered more than 117 acres of land in Kau and Puna district

- At least nine roads are now impassable.

- As many as 50 utility poles have been damaged by the lava, and hundreds have been without power since the eruptions started.

|

| steam rising from fissure 9 on Moku Street in the Leilani Estates |

|

| lava slowly advancing from fissure 16. |

And it’s not over. The US Geological Survey (USGS) warns that “additional outbreaks of lava are likely” and that steam pressure building below the surface could cause explosions raining “ballistic projectiles and ashfall” within half a mile or more from the volcano.

On Tuesday, 15 May, the volcano’s Halemaumau Crater commanded people’s attention by a display of towering ash plume from the crater that reached 12,000 feet high and could be seen for miles.

But this is not the explosion the USGS officials are warning people about since a week.

|

| dark ash plume rising from Halemaumau Crater |

According to KHON news Michelle Coombs, a geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, told reporters on Tuesday, “It intensified today, but it wasn’t the big one, so to speak. Does that mean that we won’t see a much bigger, more explosive event? No, not necessarily. It could plug up, and we could yet in the future have the so-called ‘big one.’ Today was more of a gradual ramp-up, and it was continuous enough that we felt it was significant to put out a public warning.”

Coombs added that geologists were not sure what had caused the intensified ash emissions Tuesday.

But A temporary flight restriction for 12 nautical miles around Kilauea’s summit has been put in place.

Hawaiian Volcano Observatory issued a statement on Tuesday regarding rumors about a tsunami in the Pacific Ocean, “There is no geologic evidence for past catastrophic collapses of Kilauea Volcano that would lead to a major Pacific tsunami, and such an event is extremely unlikely in the future based on monitoring of surface deformation.”

A volcano is considered potentially active if it has erupted in the past 10,000 years. America has 169 active volcanoes, mainly clustered in the West — in Hawaii, Alaska, Wyoming, Washington, and California.

There are about 1,900 potentially active volcanoes around the world, with 500 having erupted since humans have been around, according to the USGS. Some of these volcanoes may never erupt, some may ooze lava slowly for years, and some may one day have a massive ejection that wreaks havoc.

Respecting the Hawaiian legend of Pele- the goddess of fire, let’s take a more scientific look at how volcanoes are formed.

How Volcanoes are formed?

A Volcanos are formed when lava and molten rocks are squeezed in the surrounding area through a rift in the earth crust. Volcanoes vary in shapes and sizes but they all share a few key characteristics.

All volcanoes are connected to a reservoir of molten rock, called a magma chamber, below the surface of the Earth. When the pressure inside the chamber builds up, the buoyant magma travels out a surface vent or series of vents, through a central interior pipe or series of pipes. These eruptions, which vary in size, material, and explosiveness, create different types of volcanoes.

The earth crust is made up of huge blocks called tectonic plates that slide on top of the mantle. Most volcanoes form at the boundaries of Earth’s tectonic plates.

The mantle is the mostly-solid bulk of Earth’s interior that lies between earth’s dense, super-heated core and its thin outer layer, the crust. The mantle accounts for a whopping 84% of Earth’s total volume is about 2,900 kilometers (1,802 miles) thick.

The temperature of the mantle ranges from 1000° Celsius (1832° Fahrenheit) near its border with the crust, to 3700° Celsius (6692° Fahrenheit) near its border with the core.

A majority of the volcanoes of the world are all clustered in the Ring of Fire, a horseshoe-shaped string of about 425 volcanoes that edges the Pacific Ocean. But, some volcanoes exist in the middle of the oceans, thousands of miles away from the tectonic plate boundaries.

Hot spots are intensely hot areas within the surface of the earth and tectonic activity above the hot spot cause them to erupt to create a volcanic mound. Over millions of years, volcanic mounds can grow until they reach sea level and create a volcanic island. Hawaiian islands are the best example of a volcanic island in the world.

As the years' pass, the hot spot stay put, but the movement of tectonic plate cause the islands to drift apart become extinct and eventually erodes back into the ocean.

|

| The Hawaiian Emperor seamount chain is a well-known example of a large seamount and island chain created by hot-spot volcanism. Each island or submerged seamount in the chain is successively older toward the northwest. Near Hawaii, the age progression from island to island can be used to calculate the motion of the Pacific Oceanic plate toward the northwest. The youngest seamount of the Hawaiian chain is Loihi, which presently is erupting from its summit at a depth of 1000 meters. Image courtesy of U.S. Geological Survey. |

Experts think this volcanic chain of Hawaiian islands has been forming for at least 70 million years over a hot spot underneath the Pacific plate. Of all the inhabited Hawaiian Islands, Kauai is located farthest from the presumed hotspot and has the most eroded and oldest volcanic rocks, dated at 5.5 million years. Meanwhile, on the “Big Island” of Hawaii—still fueled by the hot spot—the oldest rocks are less than 0.7 million years old and volcanic activity continues to create new land.

Hawaiian Volcanoes are all exclusively made up of lava called as a shield volcano, the other being the Stratovolcanoes which are steep and conical and rising up to several thousand meters above the landscape.

Shield volcanoes are built almost exclusively of lava, which flows out in all directions during an eruption.

Shield volcanoes make up the entirety of the Hawaiian Islands. The Kilauea and Mauna Loa shield volcanoes, located on the “Big Island” of Hawaii, rise from the ocean floor more than 4,500 meters (15,000 feet) below sea level. The summit of Mauna Loa stands at 4,168 meters (13,677 feet) above sea level and more than 8,500 meters (28,000 feet) above the ocean floor, making it the world’s largest active volcano—and, by some accounts, the world’s tallest mountain.

The smaller volcano, Kilauea, has been erupting continuously since 1983, making it one of the world’s most active volcanoes.

Hawaiian lava eruptions are calmest and known for their steady lava eruptions known as lava fountains or fire fountains. The highly fluid lava associated with Hawaiian eruptions flows easily away from the volcano summit, often creating fiery rivers and lakes of lava within depressions on the surrounding landscape.

Kilauea has produced lava flows covering more than 100 square kilometers (37 square miles) on the island of Hawaii. These flows continuously destroy houses and communities in their path, while also adding new coastline to the island.

|

| Panoramic view of the lava at the end of the Chain of Craters Road, Hawaii Volcanoes National Park |

History of Kilauea eruption

|

| The Island of Hawai‘i with lava flows erupted in approximately the past 1,000 years shown in red. Located on the southeastern side, Kīlauea Volcano is 90% covered with young flows. |

|

| a 2004 Kilauea eruption, lava flowing into the sea |

The current ongoing eruption cycle began on Jan. 3, 1983, along the middle of the east rift zone. By April, the eruptions became localized at one vent. Lava fountains built a cinder and spatter cone 836 feet high (255 meters) that was named Pu`u `Ō`ō.

The frequent short eruptions produced thick chunky lava flows that usually cooled and halted before reaching the coast. However, in July 1983, the lava made its inexorable advance into the nearby Royal Gardens subdivision and destroyed 16 homes. The expensive subdivision was largely abandoned.

|

| Lava erupting from the Puʻu ʻŌʻō vent in June 1983 |

Previous to the 1983 eruptions, there were 2 more eruptions in 1955 and 1960. The eruption in 1955 lasted 88 days while the one in 1960 lasted 36 days.

Kilauea also erupted in 1986 and 1990. In 1986, lava flows cut through the town of Kalapana, on it’s way to the sea. As the lava field spread, cooled and spread again over the next three years it destroyed many homes and the Visitor Center in Hawai`i Volcanoes National Park. In March 1990, Kilauea entered its most destructive eruption period in modern history. Over the summer more than 100 homes, a church, and a store were buried beneath 50 to 80 feet (15 to 24 meters) of lava.

|

| A stream of lava from Pu‘u ‘Ō‘ō flowing through the forest in the Royal Gardens subdivision, February 28, 2008. The lava stream is about 3 m (10 ft) wide. Kīlauea Volcano, Hawai‘i. |

|

| Sulfur dioxide emissions from the Halemaʻumaʻu vent in April 2008 |

In October 2012, Lava in Halema`uma`u crater overflowed the crater's ledge and lava reached the ocean in November when it flooded the ledge of the crater. Lava flowed over the ledge again in January 2013 and continues to flow into the ocean, according to USGS.

Volcanoes are some of Earth’s most potent natural hazards and agents of change. They release enormous amounts of energy and material, engaging natural processes that can modify landscapes at a local, regional, and even global scale.

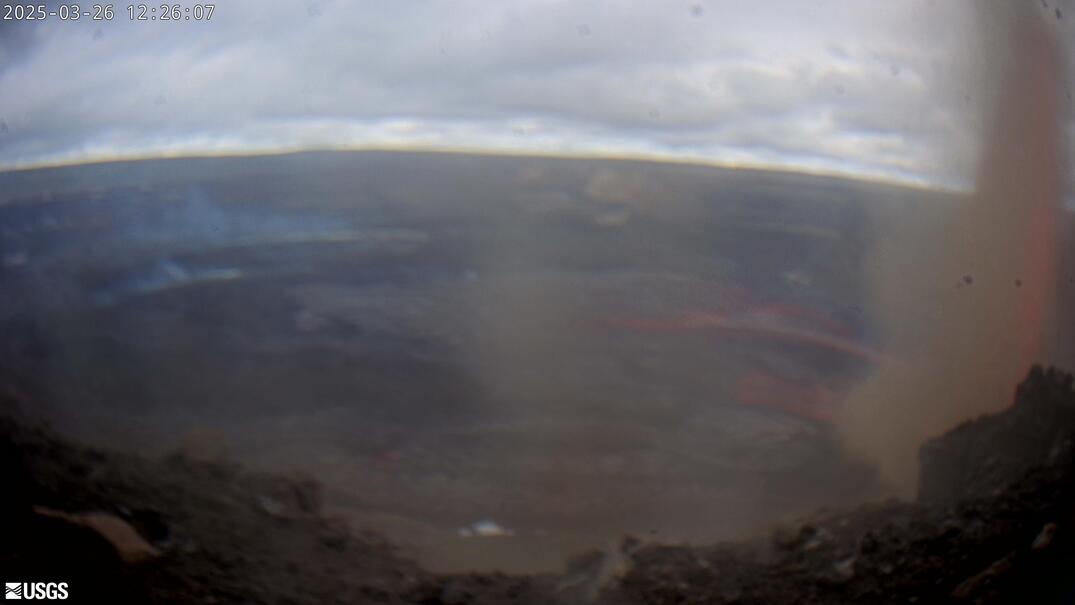

|

View upright from the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory overflight this morning at 8:25 a.m

|